- pathoferexpertise

- 0 Comments

Identification of a neuron-specific ferroptosis in the neurodegenerative mucopolysaccharidosis III model

Sanfilippo syndrome (MPSIII) is a neurodegenerative disorder caused by enzyme deficiencies, leading to the toxic accumulation of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides in the brain. Emerging evidence suggests that ferroptosis, an iron-dependent form of cell death, contribute to neurodegeneration. To investigate ferroptosis in MPSIIIB, we examined its regulatory mechanisms and markers in MPSIIIB brains. Our results showed elevated iron levels, decreased mRNA expression of TFR1 and ZIP14 (involved in iron uptake) at 9 months of age, and increased protein levels of FTH (which stores intracellular iron) in MPSIIIB brains, indicating a potential link to ferroptosis. We also observed diminished levels of ferroptosis-neutralizing proteins (xc-/GPX4), while the protective pathway (Keap1-Nrf2) was activated. Oxidative homeostasis disruption was revealed by increased expression of genes encoding SOD2, SIRT3, iNOS, and nNOS enzymes. Increased expression of lipid peroxidation genes (ascl4 and lpcat3) further supported ferroptosis involvement. Furthermore, we analyzed protein abundance and brain immunostaining of the iron exporter FPN. Despite its high expression levels, this protein appeared misfolded and was insufficiently targeted to cellular plasma membrane, which might contribute to cellular iron retention. The co-localization of FPN with NeuN, a marker of neurons, demonstrates that only neurons are affected by this targeting defect, suggesting neuronal ferroptosis specifically in MPSIIIB. Overall, our findings evidenced of the involvement of ferroptosis in MPSIIIB pathogenesis, highlighting dysregulation in iron homeostasis, antioxidant defenses, and lipid peroxidation as key features of the disease.

1-Introduction

Sanfilippo Syndrome, also known as mucopolysaccharidosis type III (MPS III), is a rare genetic disorder characterized by the deficiency of specific enzymes required for the degradation pathway of heparan sulfate, a type of glycosaminoglycan (GAG). Theses enzyme deficiencies lead to the accumulation of heparan sulfate oligosaccharides (HSO) in various tissues, particularly in the brain, resulting in cellular dysfunction and progressive neurodegeneration (Neufeld and Muenzer, 2001). The four distinct subtypes of MPSIII (A, B, C and D, each corresponding to a specific enzyme deficiency) exhibited common features including developmental regression, hyperactivity, sleep disorders and distinct somatic abnormalities.

The links between the accumulation of HSO and the neurodegeneration observed in patients have been extensively explored over the past few years. Neuroinflammation have been identified as one of the hallmarks of MPS III pathogenesis in both patients and the mouse models. In the mouse brain, microglia and astrocytes are early responders, and microgliosis has also been described (Ohmi et al., 2003; DiRosario et al., 2009; Holley et al., 2018). HSO has been found to act as a ligand for Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) and mediates the activation of microglia as early as 10 days in MPS IIIB mice (Ausseil et al., 2008), suggesting that HSO primed microglia early in the course of the disease. We also demonstrated that activated microglia can impact neurons via inflammatory cytokines (Puy et al., 2018); however, the pathogenic mechanisms driving the neurodegenerative process in neurons remain to be identified.

Ferroptosis, prevented by iron chelation, is a form of regulated cell death characterized by the iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides within the cell membrane (Dixon et al., 2012). This distinctive mode of cell death has received significant attention in recent years due to its implications in various neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, and multiple sclerosis, where iron accumulates due to intrinsic dysregulation of iron metabolism in the brain (Weiland et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2023).

Acquisition of iron by the brain is particular since the blood–brain barrier separates the CNS from the systemic circulation and brain cells do not have direct access to blood transferrin (Tf)-bound iron. Iron must first enter the brain through microvascular endothelial cells in a multi-step transcellular pathway and an endogenous Tf synthesis is required to facilitates brain cells iron uptake via TF-receptor (TFR1)-mediated endocytosis. Yet, levels of apo-transferrin in the brain interstitium are quite low such that Tf become saturated with small amounts of iron and non-Tf bound iron (NTBI, the most toxic iron form) appears as the main source of iron delivery to neural cells. By comparison to systemic NTBI that is transported in the liver by the metal-ion transporter ZIP14 a member of ZIP (Zrt- and Irt-like Protein) family, handling of NTBI into brain cells is believed to be mediated by divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT-1), although ZIP14 is also expressed in the brain. Iron storage in brain cells is classily mediated by intracellular ferritin cores. Abnormalities in iron metabolism regulation, such as iron overload or dysregulation of proteins involved in iron management (e.g., transferrin, ferritin), can increase the availability of free iron within the cell. This free iron, not bound to proteins, is particularly reactive and actively participates in Fenton reactions, which produce highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH•) from hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), causing lipid peroxidation, damaging cellular membranes and contributing to ferroptosis.

Previous clinical investigations have revealed a notable increase in iron deposition within anatomical regions pertinent to motor function (e.g., globus pallidus) and extrinsic sensory processing (e.g., pulvinar region) in two siblings with MPSIIIB (Brady et al., 2013). These data were confirmed in the parietal cortex of MPSIIIB mice (Puy et al., 2018), which was concomitant with the onset of neuroinflammation (Villani et al., 2009) and oxidative stress in the brain (Trudel et al., 2015).

Thus, the collective evidence of cerebral iron accumulation indicates that iron-associated neuropathology may serve as additional factor implicated in the neurodegenerative process of MPSIII.

In this article, we aim to further elucidate eventual presence of ferroptosis mechanisms in the murine model for type B of Sanfilippo Syndrome.

2-Materials and methods

2.1 Animal model C57Bl/6 Naglu−/− (MPSIIIB) mice were purchased from Jax Lab (stain ref #003827). This model was initially obtained by introducing a neomycin resistance cassette into the exon 6 of Naglu gene, interrupting therefore the production of full length active NAGLU enzyme (Li et al., 1999). The experiments were conducted in male and female wildtype (WT) and MPSIIIB mice, ensuring that we included an equal number of males and females in each experiment whenever possible. They were fed standard laboratory chow for 2 or 9 months, with food and water provided ad libitum. All experiments were performed in accordance with European Committee Standards concerning the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the local ethical committee (n°122) and by the French Ministry of Higher Education and Research (n° 2020273122248406V4). 2.2 Mouse brain tissue processing The mice were first subjected to euthanasia by injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. Blood samples were then collected by cardiac puncture, and brains were removed after heart perfusion with PBS. Isolated brains, were either harvested and frozen at −80°C for further analysis, or immediately processed for immunohistochemistry processing. 2.3 Brain sections immunohistochemistry Brain samples were embedded in paraffin and sectioned into 5 µm slices. The brain sections were then deparaffinized and rehydrated using histoclearII® baths and antigen retrieval was performed using microwave heated 1x citrate buffer. The sections were then incubated with blocking solution (HRP008DAB, Zytomed) and with peroxide block solution (E41-100, Diagomics) to avoid non-specific binding of antibodies or of 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB) staining. Primary antibodies were used at 1:400 dilutions for anti-FPN (P1-21502, Novus Biological) and anti-FTH (DF6278, Affinity Biotech). The immunoreactive staining were revealed with the streptadivin-HRP conjugated secondary antibodies and DAB solution. 2.4 Tissue iron quantification 100 mg of these brain tissues were cut into 4 to 6 pieces using a non-metallic scalpel. They were placed in a microtube washed with 0.5 M HCl. After adding 400 µL of protein precipitation solution (H20, trichloroacetic acid, HCl C°36%–38%, Thioglycolic acid), the samples were placed in a double boiler at 65°C for at least 24 h. Once the liquid supernatant had been recovered and weighed, the equilibration solution (sodium acetate pH4.5) diluted 1:10 was added. The concentration of ferric iron, including free and bound iron, was then measured using an automated system (Kit Iron #SI8330, Ferrozine, Rendox Daytona+, Randox Laboratories, France). 2.5 RNA extraction and reverse transcriptase-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) Total RNA was isolated using the SV Total RNA Isolation System Kit (Z3103, Promega) according to the supplier’s recommendations. The reverse transcription reaction was performed using 1.5 µg of total RNA in a final volume of 20 μL. qPCR was performed in duplicate using the SsoFast EvaGreeen PCR-mix (1725204, BioRad) and specific primers for TLR4, ZIP14, iNOS, nNOS, SIRT3, SOD2, ACSL4, LPCAT3 and ARPO transcripts (Table 1). Results were normalised to transcripts of the brain specific ARPO housekeeping gene. Results were expressed in arbitrary units as a fold change relative to the control sample using a 2−ΔΔCT calculation (ΔΔCt = ΔCt exposed − mean ΔCt control). qPCR and statistical analyses were performed using StepOne Software v2.3 and PRISM (Prism 10 Version 10.1.1).Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

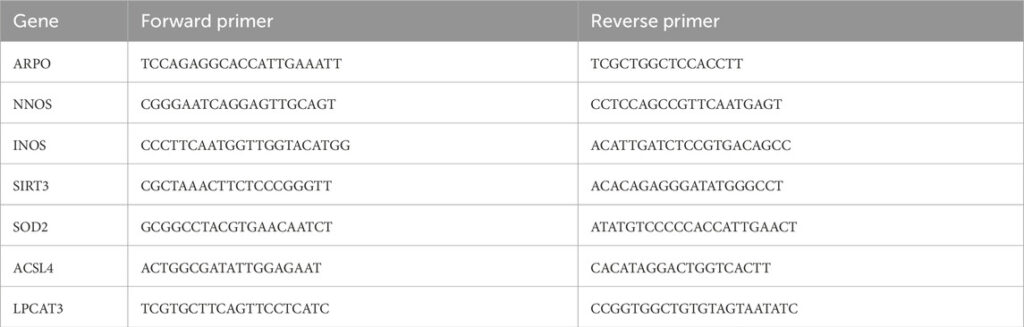

Primers used for RT-qPCR amplifications of genes.

2.6 Proteins extraction and western blotting (WB)

Brain tissue samples were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 250 mM sucrose, 30 mM histidine, 1x inhibitor cocktail and 0.1 mM 4-2-aminoethylbenzenesulfonyl fluoride (AEBSF), using an ultraturax at 4°C. Membrane proteins were purified by an initial centrifugation of the homogenate (2,200 rpm, 5 min at 4°C), and second ultracentrifugation (45,000 rpm for 1 h at 4°C) of the supernatant. The resulting pellet, was resuspended using a 27G needle and protein assay was performed using the Pierce TM Rapid Gold BCA Protein Assay kit according to the supplier’s recommendations (A53225, ThermoFisher). For Western blot analysis, 30 µg of proteins was separated on 4%–15% SDS-polyacrylamide pre-cast gels (Mini-PROTEAN® TGX™ Precast Gels, BioRad) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the Trans-Blot® Turbo™ Transfer System (1704150, BioRad). Primary antibodies were used at 1:2000 dilutions for anti-FPN (#NBP1-21502SS, Novus Biologicals Europe, Abingdon, United Kingdom) and 1:1000 for the following antibodies: anti-FTH (#A19544, ABclonal, Düsseldorf, Germany), anti- xc- (#DF12509, Affinity Bioscience, Europe), anti-NRF2 (#AF0639, Affinity Bioscience, Europe), anti-GPX4 (#A11243, ABclonal, Düsseldorf, Germany), anti-Keap1 (#AF5266, Affinity Bioscience, Europe), anti-SOD2 (#AF5144, Affinity Bioscience, Europe). Finally, to reveal the immunolabelled proteins, the luminol-peroxidase solution (#RPN2232, Cytiva) was deposited on the membrane before being observed on the ChemiDoc Imaging System XRS + sampler (#1708265, BioRad). The results are standardized by dividing the value of the density of the band of interest over the value of the total proteins in the same sample (Supplementary Figure S1). Analyses were carried out using ImageJ software (ImajeJ2 version 2.14.0/1.54F). The complete immunoblot images presented in this article, along with their corresponding total protein staining, have been submitted to the journal for standard verification.

2.7 Statistical analysis

For all samples, we performed Mann-Whitney tests, which is a non-parametric test using GraphPad Prism software (Prism 10 Version 10.1.1) setting the statistical significance threshold at p < 0.05. Values were expressed as mean ± SEM.

Normalized quantification data both for WB and RTqPCR and reported in Supplementary Tables.

3-Results

Ferroptosis is a regulated form of cell death characterized by the accumulation of iron and lipid peroxides. Several markers and characteristics are used to identify the presence of ferroptosis in cells. The main ones are accumulation of iron, accumulation of lipid Peroxides highlighted by overexpression of ACSL4 (long-chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4) and LPCAT3 (lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3) genes, molecular and enzymatic markers such as reduced GPX4 (Glutathione Peroxidase 4), a key enzyme that protects against lipid peroxidation, decreased SLC7A11 (xc−), the subunit of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system that regulates cystine import for glutathione synthesis, and finally induced anti-oxidant systems including SOD (superoxide dismutase), SIRT3 (sirtuin 3), NRF2 (Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2). We therefore studied all these markers in MPSIIIB by comparison to WT mice at 2 and 9 months of age.

3.1 Iron accumulation of MPSIIIB brain

We have previously demonstrated that total iron content progressively accumulates in the MPSIIIB mouse brain, becoming significant by 9 months of age. This accumulation was particularly pronounced in the cortex region. Figure 1A presents the quantification of iron in the total brain at 9 months. The results indicated that the increase in iron content was still significant compared to the WT brain, although the magnitude of this increase was smaller compared to the cortex (Figure 1A and (Puy et al., 2018)).